Walk LaSalle Street at dusk and the old canyon feels different. The lobby lights are on longer. You hear construction lifts, not just echoing footsteps. It’s a quiet shift, but it’s real: the city’s central business district (CBD) is moving from a 9-to-5 office core toward a mixed-use neighborhood, built not by demolition but by adaptive reuse. For anyone who follows Chicago real estate, this corridor has become the city’s most revealing experiment in how to turn vacancy into vitality.

Vacancy Shock and a Policy Response

By late 2024, Loop office vacancy hovered near 27 percent, the highest since the 1990s. Whole floors sat dark; property tax revenue softened; retail thinned. Rather than chase another leasing cycle, the city created LaSalle Street Reimagined—a competition inviting developers to transform obsolete offices into housing. Through the LaSalle Central Tax Increment Financing (TIF) district, the city helps close funding gaps if at least 30 percent of units remain affordable to households earning about 60 percent of Area Median Income (AMI)—roughly $50,000 for a two-person household.

That single rule reframed who can live downtown and set the tone for what comes next: a real, mixed-income neighborhood in the heart of the Loop.

In an interview with Loop Chicago, DPD Commissioner Maurice Cox explained the city’s vision clearly:

“As the Loop population continues to grow and the market leverages new housing opportunities in underutilized commercial spaces, these projects are laying a foundation for a dynamic, mixed-use corridor that serves all Chicagoans, regardless of their incomes.”

If you’ve read From Skyscrapers to Empty Floors: What Chicago’s Office Comeback Struggle Means for City Life in 2025 or Chicago 2025: How Downtown Decline & Neighborhood Revival Are Redrawing Where People Live, this new phase makes sense. Adaptive reuse is no longer theory—it’s policy.

The Tool That Makes Conversions Work

Turning a 1930s landmark into apartments means gutting deep floorplates, inserting new plumbing risers, and preserving heritage façades. Few projects pencil out without help. TIF financing fills that gap: property-tax growth generated after completion repays the subsidy. The city exchanges that help for on-site affordable homes and active street fronts. Developers layer in federal historic tax credits and traditional debt.

For a breakdown of how this fits the broader budget strategy, see Chicago’s 2026 Budget Showdown: New Taxes, Tech Levies & Who Ultimately Pays for the City’s Comeback—it explains why the Loop’s real estate recovery depends on public-private math.

Five Flagship Conversions Bringing Homes to LaSalle

Below are the projects driving this transformation. Figures come from City of Chicago, CTBUH, and World Business Chicago.

| Address & Name | Developer / Lead | Total Units | Affordable Units (~30%) | TIF Support (USD M) | Notable Features / Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 135 S. LaSalle (The Field Building) | Prime Group & CRG | ~386 | ~116 | 98 | Art Deco landmark with preserved lobby; retail & amenity space; construction 2025 → 2027 |

| 208 S. LaSalle | Beal Properties | 226 | 68 | 26 | Former bank & hotel tower converted to apartments; early 2026 delivery |

| 30 N. LaSalle | Golub & Walton | 349 | 105 | 57 | Ground-floor dog run, terrace, streetscape upgrade planned 2026 |

| 111 W. Monroe | Prime Group | 345 | 105 | 40 | Hybrid hotel + residences; preserves historic bank hall for public use |

| 79 W. Monroe | Cambridge Development | 117 | 41 | 28 | Smaller retrofit within existing floors; model for incremental reuse |

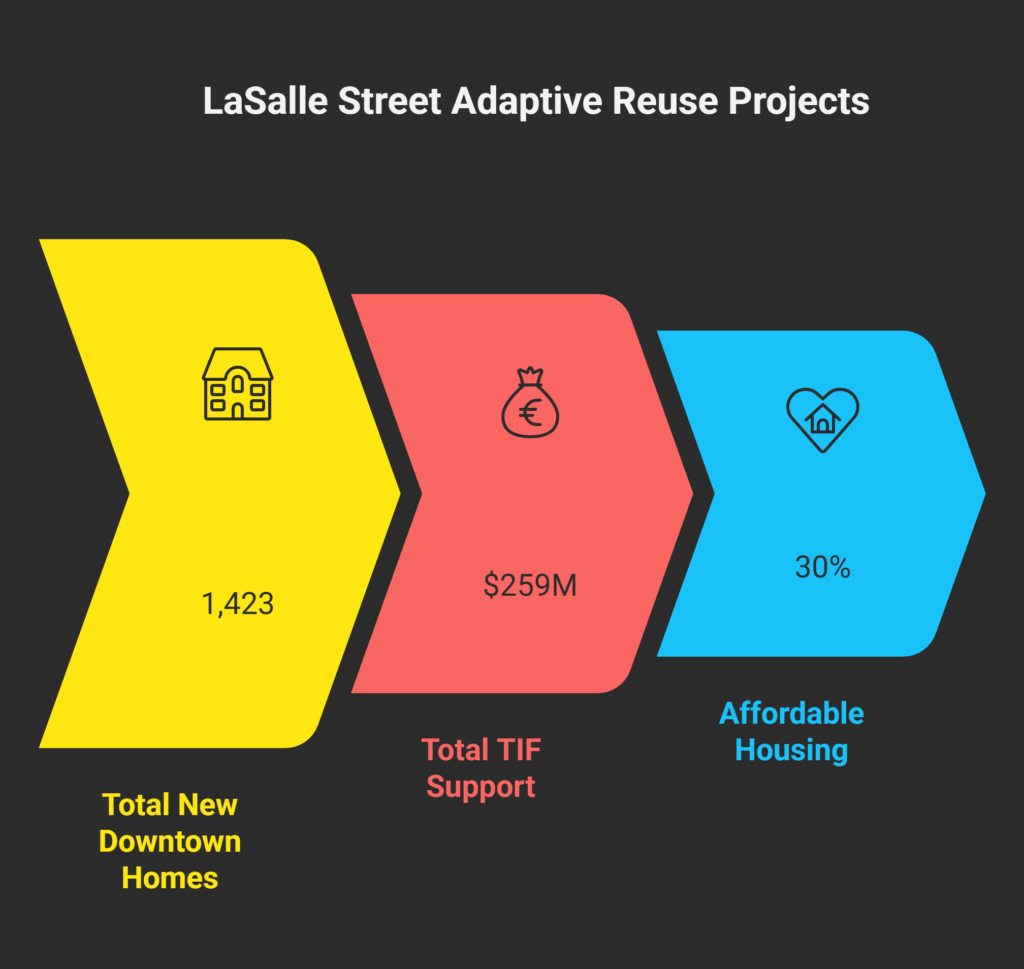

Together, these represent 1,423 homes—over 430 affordable—and roughly $259 million in TIF. Average subsidy per affordable unit runs around $590 k, high but typical for landmark conversions. Critics question cost; advocates see it as the price of keeping the city’s historic spine alive.

Street-Level Reality: From Office Canyon to Mixed-Use Main Street

The fastest way to feel progress is simply to walk LaSalle. Weekdays still sound like business: pinstripes, brisk steps, the CTA LaSalle/Van Buren platform humming, trains sliding into the Metra LaSalle Street Station. But weekends have changed. Chicago Loop Alliance data show Saturday foot-traffic exceeding 2019 levels while weekday counts trail. Restaurants that once closed at 2 p.m. now keep dinner hours. You see grocery bags instead of briefcases, runners on Monroe, dog-walkers circling Adams.

In an interview with the Chicago Sun-Times, Michael Edwards, president of the Chicago Loop Alliance, described what he’s seeing:

“My big takeaway is that downtown is back… These buildings will become more attractive.”

He echoed that optimism in a Loop Chicago statement:

“Diversifying vacant storefronts invites pedestrians to interact with the corridor and encourages further utilization of a vital sector of the Loop community.”

To support that life, CDOT and DPD are planning streetscape improvements—better lighting, added greenery, more seating, and curb designs that invite outdoor patios. At 30 N. LaSalle, renderings show a pocket park and dog run, small touches that signal this isn’t just adaptive reuse; it’s urban repair.

For a design-culture view of how architecture drives civic mood, read How Architecture and Design Are Rebuilding Chicago’s Creative Identity in 2025—many of the same ideas are materializing here in brick and limestone.

Lived Experience: Commute, Safety, and Everyday Life

Residents who already live nearby describe the appeal plainly: order, convenience, architecture. The commute is unbeatable—trains in every direction within three blocks, a ten-minute walk to the river or Millennium Station.

Safety has followed visibility. More homes mean more “eyes on the street.” Light spilling from new lobbies and corner cafés does what policy alone can’t: it makes people comfortable after dark.

Future appreciation looks steady, not speculative. As adaptive-reuse inventory fills, rents stabilize and nearby retail leases pick up. Historically, mixed-use conversions in Chicago’s core (think South Loop or River North) have shown gradual but durable value growth once the first residential wave matures.

What residents still want are third places—neighborhood cafés, groceries, and local bars that make daily life frictionless. City planners expect those to follow within a year of occupancy.

If affordability is top of mind, compare this with Why Avondale Is Chicago’s Fastest-Rising Neighborhood — And What It Means for Affordable Living to see how different sub-markets handle cost, transit, and community feel.

The Quiet Math — and Its Critics

Every conversion mixes ambition with arithmetic. Developers see an equation of construction cost, rent ceiling, and preservation mandate. The public sees a social contract: $1 of subsidy should create $1 of visible civic value.

Skeptics note that the subsidy per affordable unit—often $500 k to $600 k—is steep, while advocates argue that stabilizing property-tax revenue and converting obsolete offices are worth the price. The City of Chicago’s DPD maintains that TIF proceeds will be recaptured through higher assessments once the corridor re-leases retail and raises occupancy. Early modeling by CTBUH suggests about $5.8 million in new annual property tax revenue once these projects stabilize.

For national perspective, Urban Land Institute covers similar programs in New York and San Francisco—Chicago’s version stands out for its affordability requirement and preservation goals.

Getting Around and Living the Loop

Life here runs on trains, feet, and small conveniences. The CTA Loop L lines, Metra Rock Island District, Divvy bikes, and walkability make car-free living realistic. That accessibility lowers total housing cost and strengthens long-term demand—critical for both renters and investors watching future appreciation.

For families or couples balancing lifestyle with commute, the Loop offers ten-minute rides to UIC, DePaul’s downtown campus, and South Loop schools. Public schools aren’t the area’s draw yet, but nearby selective-enrollment options and private academies provide workable choices.

2026–2027: What “Delivered” Will Look Like

By mid-2026, cranes will taper off and leasing banners will go up. Expect:

- 1,400 new apartments completed or under lease

- 400 + affordable units integrated on site

- Street-level retail activation in at least three major towers

- Reopened historic lobbies doubling as public space

- Roughly $5–6 million in added annual property tax revenue

By 2027, the corridor should feel lived in seven days a week: morning joggers, lunch crowds, twilight dog-walkers, and neighbors meeting outside cafés. It won’t be dramatic—but that’s Chicago’s rhythm: transformation by accumulation.